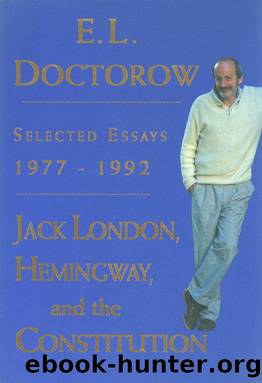

Jack London, Hemingway, and the Constitution by E.L. Doctorow

Author:E.L. Doctorow [Doctorow, E. L.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 978-0-307-79977-7

Publisher: Random House Publishing Group

Published: 2011-07-18T16:00:00+00:00

THE BELIEFS OF

WRITERS

All writers relish stories from the lives of the masters. We hold them in our minds as a kind of trade lore. We hope the biography of the great writer yields secrets of his achievement. As many writers as Hemingway inspired to write he probably inspired to hunt or to box. I imagine many of them crouching this very moment in their duck blinds. Writers always want to learn how to live as a means of bringing out the best they have in themselves.

The masterâs life Iâve been thinking about lately is Tolstoyâs, in particular his crisis of conscience at the age of fifty. Always at the mercy either of his passions or his ethics, Tolstoy lived in a kind of alternating current of tormented resolution. The practice of fiction left him elated and terribly let down. Itâs said that he had to be prevented from throwing the finished manuscript of Anna Karenina into the fire. In any event, at the age of fifty he decided that his life lacked justification, that he was no better than a pander to people who had nothing better to do with their time than to read. And he gave up writing novels.

Of course, his resolve did not seem to cover the shorter form, and over the years he lapsed into the composition of a few modest piecesââThe Kreutzer Sonata,â âThe Death of Ivan Ilyichââbut for the most part he employed his position and his talents to militate against some of the overwhelming misery of life under the czar. He indulged a prophetic voice. He preached his doctrine of Christian nonviolence. He wrote primers designed to teach the children of peasants to read.

Now theoretically, at least, there is for every writer a point at which he or she might come to the same conclusion as Tolstoy, a point at which circumstantial reality overwhelms the very idea of art or seems to demand a practical benefit from it; when the level of perceived or felt communal suffering or danger makes the traditional practice of literature for traditional purposes intolerable. But even a casual examination of literary history finds a readier disposition for this crisis of faith in Europe, where the passion of art has often been a social passion. So in Russia we have not only the example of Count Tolstoy stomping around in his peasant boots but the young Dostoevsky and his circle arguing everything about fiction except its enormous importance to history and human salvation. And in France we have Sartre and Camus, among others, conceiving a response to the moral devastation of World War II, a literary Resistance that includes drama, allegory, metaphysics, and handing out pamphlets in the streets.

With certain exceptions, American writers have tended to be less fervent about the social value of art and therefore less vulnerable to crises of conscience. The spiritual problems of our writers are celebrated but of a different kind from those having to do with the problem of engagement. Our nineteenth-century masters lived in sparse populations.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12360)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7743)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7309)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5745)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5733)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5400)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5067)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4924)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4712)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4558)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4541)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4507)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4430)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4084)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4013)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3998)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3982)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3965)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3836)